I have now completed the course from Future Learn (2019), supported by Leeds University. This course was a Massive Online Open Course (MOOC) on Blended Learning Essentials. The intention of taking this course was to supplement my MA Education Ed Tech module.

The course started on 18 February 2019 and was a 5 week, so should have been completed by 25 March 2019. I could say that there were mitigating circumstances why I took until 7 May 2019, but in reality I was not dedicated to this course, as there was not a compelling reason to continue, other than I had posted it on my blog as I was reviewing it. Plus, I paid for the upgrade!

I did not have colleagues or any peers on the course, so as Wenger 2009 suggests regarding Communities of Practice and Guldberg and Mackness (2009) with the online Communities of Learning, there was not common domain and thus no bond built up, physical or otherwise, to pull me in and make me feel part of a community.

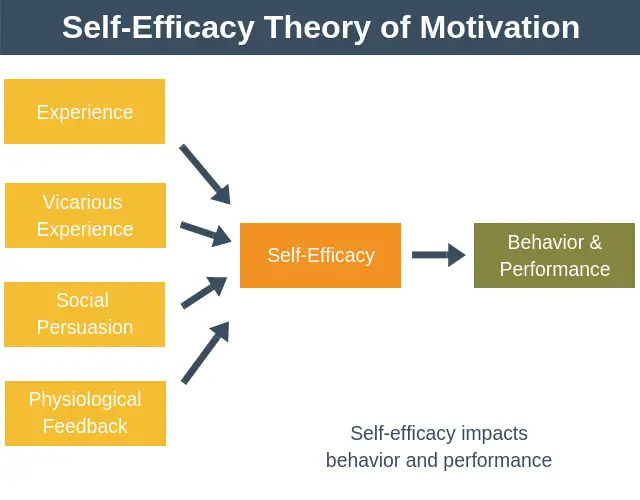

Thus I hand no self-efficacy which caused me to be demotivated (see below). This then becomes hard to pick up and complete because time has passed. Other participants will have blogged in the correct weeks session on the content. Thus, causing the course to feel somewhat irrelevant. In self-efficacy theory the beliefs become a primary, explicit explanation for motivation (Bandura, 1977, 1986, 1997).

Self-Efficacy Theory of Motivation

A comment in an article “Moocs struggle to lift rock-bottom completion rates” in the Finacial Times By Murry (2019) on MOOCs states this about completion rates:

“Much of the early enthusiasm for massive open online courses, or Moocs, focused on how they could disrupt and democratise education — opening elite universities’ courses to the masses. They have long faced one stumbling block, however: barely anyone who starts a Mooc completes it ” Murry (2019)

This statement on the MOOCs is echoed by Harber (2012) when the first MOOC s started to appear and were though to be the new age in online education.

The information on low completion rates was determined after a report on MOOCs by Reich and Ruipérez-Valiente (2019 who discussed this issue. They state that only 52% of those who signed up started and the rates of attrition remind high in the first few weeks, with only 4% completing a course. Some people however, do go on to a full university degree, but these people were already undertaking a course or in education. They have just not had the impact on education that was anticipated (Harber 2012).

This sums up my situation and makes me feel privileged to have participated and completed my MOOC course, given the low completion rates. All be it a little protracted! I did achieve and receive my certificate.

References

Bandura, A. (1977). Self-efficacy: Toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychological Review, 84, 191–215.

Bandura, A. (1986). Social foundations of thought and action: A social cognitive theory. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Bandura, A. (1997). Self-efficacy: The exercise of control. New York: Freeman.

Future Learn (2019) Blended Learning Essentials. [Online] Available at Future Learn Accessed 5-5-19

Guldberg, K. and Mackness, J. (2009). Foundations of communities of practice: Enablers and barriers to participation, Journal of Computer Assisted Learning, 25:6, 528–538.

Harber, J., (2014) MOOCs. London, MIT Press. Google Books

Murry, S., (2019). Moocs struggle to lift rock-bottom completion rates. London. Financial Times.

Reich, J. and Ruipérez-Valiente, J. A. (2019). The MOOC Pivot. Science 363(6423), pages 130-131.

Wenger, E., (2009). Social Theory of Learning. Chp 15, Contemporary Theories of Learning, Learning Theorists …. in Their own words. Ed., Illeris, K., Routledge, London