My new journal article published on 11 March 2024 via AchievAbility E-Journal | Issue 4 | Winter 2023 | 4. The Article in the journal here and below.

This article explores the differences and similarities between generations, whether there is collaborative support and, if so, what this entails. This supposition evokes thoughts of the position I find myself in as a mature neurodivergent student who also works as a non-medical

helper (NMH), provided by Disabled Students Allowance (DSA), supporting autistic undergraduates at university.

Education sets the context for the article, in addition to my professional standpoint as a

teacher and personal perspective as a mature neurodivergent (dyslexic) academic. The discussion of the generational divide is accomplished by using the qualitative paradigm and the

method of autoethnography to support my self-reflection by examining the intersections between the ‘Self as a Social Construct’ that helps me understand my objective world as suggested by Gergen (2016:110). In addition, the political and cultural customs and expectations that are entrenched in personal experiences at university with ‘Education as a Social Construction’ as ndicated by Dragonas, et. al., (2015: ix) is used. This supports me in representing the experience of the younger generation of autistic university students as they unravel their understanding of themselves (Adams et al., 2017; Ellis et al., 2011; McIlveen, 2008; Méndez, 2014; Wall, 2006).

This leads in turn to comparing and contrasting what similarities and differences the generations have whilst considering if, in these social constructs, we are collaborative and supportive of each other using a further social construct of ‘Generational Theory’ as denoted by Strauss and Howe (1991).

I conclude with whether this works for me and the students I support in an educational context,

considering the generational differences. Additionally, could this be applied to a wider generational context of generations which are supportive and collaborative?

Autoethnography As Essay Methodology

To undertake this introspection, I used the qualitative methodology of autoethnography defined by Wall (2006:146):

“[…] a qualitative research method that allows the author to write in a highly personalised style, drawing on his or her experience to extend understanding about a societal phenomenon.“

This is extended by Adams et al., (2017) who suggest that it offers accounts of personal experience (auto) that are reflective, informing readers by describing and interpreting (graphy) aspects of cultural life (ethno) that others may not be aware of. Furthermore, Méndez (2014) points out that an autoethnographic stance has advantages as the narrative is readily

available and Ellis and Adams (2014: 254) state, “personal experience, acknowledging existing research, understanding and critiquing cultural experience, using insider knowledge” supports this notion.

Non-Medical Helper (NMH)

My role as NMH is personal one-to-one bespoke support (study skills, mentoring and assistive technology training) provided to students with a disability, such as autism in this instance, as defined in the Equality Act 2010.

To access this support, they need to be awarded a DSA grant by Student Finance England (SFE, 2022) which helps with the extra costs of support. This is paid directly to the NMH Provider who employs me (SFE, 2022) to enable access to their studies more equitably.

However, to access this grant autistic students need to have a clinical diagnosis of autism, which is a lifelong neurodevelopmental condition affecting them behaviorally, socially, emotionally, and academically at university, with strengths and limitations (Bolourian et al., 2018). The use of diagnosis first language will be used in this article as it is preferred by those with autism because it is a concealed disability that is part of their persona (Dunn and Andrews, 2015). The diagnosis is a requirement to apply for DSA because evidence of the disability has to be provided with the application.

Having a diagnosis and being labelled follows the ‘Medical Model’ of disability as a ‘condition’, that needs appropriate ‘treatment’ as stated by Llewellyn & Hogan, (2000:158). Yet, in my NMH support role, I am advised to follow the ‘Social Model’ by Haegele & Hodge (2016:197) suggesting that it is “not one’s bodily function that limits his/her abilities, it is society”. I subscribe to a more nuanced balanced approach to students’ differences, creating a bespoke

Individual Learning Plan (ILP) for them based on the specific requirements they wish to share with me (Berghs et al., 2016). As a neurodivergent person supporting them, I feel I can be more nuanced and share with them my differences, expertise and experiences professionally, so that they may begin to trust and respect me as a mature person. Still, a limitation may be that honesty, self-disclosure and validity must be carefully considered (Mendez, 2014). However, this helps me carefully reflect on my NMH helper role within the university culture, being an academic myself supporting the autistic undergraduates on DSA, and share my insight.

To accomplish this, I draw on my lifelong experiences of work, and in-depth knowledge as an academic, teacher, professional, parent and mature person spanning several generations. I listen carefully in my supporting role during the planned sessions by being open-minded to their needs and taking time to engage them on a common ground. In addition, I share my experiences and differences whilst maintaining professional boundaries.

Reflecting on my NMH role the respect and trust that I gain from young autistic students, who are more than a generation apart, are due to me sharing my recent academic understanding as a doctoral student. Additionally, I use the experience of my prior qualifications and my accredited knowledge of autism, as an ally and advocate (Martin, 2020). Moreover, as I deliver study skills support, mentoring and assistive technology this gives me an all-around perspective of every aspect of support. However, on further reflection, I feel it is not only this that puts them

at ease enabling them to engage with me. It is that I am not judgmental or condescending, treating them equally, giving praise, encouragement and practical advice irrespective of the disclosure of their neurodivergence, culture, identity, or sexual orientation (Cooper et al., 2017).

Furthermore, I take time to ask if there are resources they have that help them, giving them time to reciprocate creating active learning and engagement with social interaction to help build a “social identity” as stated by Cooper et al., (2017: 845) that they can find difficult. They appreciate me taking the time to listen and share resources with me. Additionally, knowing the culture of the university enables me to signpost them to services within and outside the

university when this is required or outside my remit (Hillier et al., 2018); this also supports them to self-advocate.

Having provided this support for nearly 5 years, I have neither encountered prejudice nor barriers being a mature person or experienced not providing them with the support they need as a much younger generation. This is reciprocated as I have been sent many messages from the students telling me how well they have done and thanking me for my support. Information on the support in a NMH role and the requirements are on the Student Finance England (SFE, 2023) website. This is mainly professional memberships as a qualified teacher (Department for Education, 2023) and The Ask Autism Training by the National Autistic Society (NAS, 2019) to

specifically support autistic students.

A Comparison of Generational Differences and Similarities

To expand on the notion of the generational differences and similarities that I experience in the

context of this article, the culture of university study, research and academic requirements, there needs to be an understanding of what is considered a generation and why.

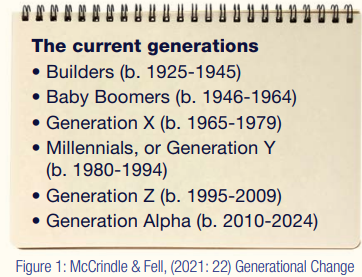

In Figure 1, above, from the recent book by McCrindle and Fell (2021), initiated by the ‘Generation Theory’ of Strauss & Howe (1991: 32), are the colloquialisms for the generations.

There have been naming variations for these cohorts. Furthermore, Kingstone (2021) and Rudolph et al., (2021) both suggest that this is a “socially constructed concept” that can be due to age, culture, and common historical events and experiences that occur during a generation up to the age of 20, for example, political events, war or more recently the Covid-19 pandemic, in addition to the social constructs of education and self (Dragonas, et. al., 2015 and Gergen, 2016).

There is contention around the Generational Theory which has been used in the main to compartmentalise the generations for employment needs by businesses which gave rise to labelling, stereotyping and discrimination (Parry & Urwin, 2011). This has however, over the last 10 years, gradually begun to be eroded with organisational training, guidance and employment tools with awareness campaigns from the UK Government with the Autism Strategy 2021,

as reported by HM Government (2021).

In this generational construct, I am in the ‘Baby Boomer’ generation whereas the students I support will likely be in ‘Generation Z’, two generations apart from me. In considering the generational differences as discussed, this suggests I would be significantly different to them due to the period I grew up in. Yet in the current context of a cohort in academic study, they are more similar to me than those of my generation as discussed by Parry & Urwin (2011: 79) who suggest there is a need to “first to disentangle cohort and generational effects from those caused by age or period”, which indicates a similarity not based on generation, but similarity of interest. This appears to put me at a different advantage because I am aware of the ‘Generation Z’ life experiences, whereas they have not experienced most of mine, but the similarities of the recent Covid-19 pandemic and study are common to us both (Parry & Urwin, 2011).

My role of NHM and academic surpasses the notion of generation and similarities, floating undeterred by age, mine and theirs, which “debunks the notion of a generation” as stated by Rudolph et al., (2021:946) who further suggest that lifespan should be considered:

“The lifespan perspective is a well-established alternative to thinking about the process of ageing and development that does not require one to think in terms of generations. The lifespan perspective frames human development as a lifelong process which is affected by various influences – not including generations – that predict developmental outcomes.”

However, younger minds in ‘Generation Z’ are far more malleable and accepting of new and varied ideas such as the new Artificial Intelligence (AI) that is gaining traction in a digital world (Costa et al., 2019; Gunduzalp, 2021; Lyashenko & Frolova, 2014). Being a ‘Baby Boomer’, I need to make sure that this difference does not cause a ‘Digital Divide’ by keeping up my ‘Digital Practices’ with assistive technology as noted by Costa et al., (2019: 567). Yet it should be noted that the digital age has changed research, perspectives and attitudes, but also caused stress anxiety and sometimes addictive use of the internet, especially for autistic students (Shane-Simpson et al., 2016). This is different to my need to use the internet purely for work and study because the internet only became part of my generation in the ’90s. However, I do need

to try and “keep up with this younger generation” as noted by Costa et al., (2019: 566). So, there are some generational similarities across my lifespan and differences between a teacher and students with a common ground to work on via digital tools and academic study (Gunduzalp, 2021).

Is there collaboration and support between the generations?

Before undertaking research information for this article, I had not considered if there was collaboration and reciprocal support between myself as an NMH and the autistic students. Yet once I started to reflect on our interactions in the learning and support sessions, and on messages and emails, I realised that there was far more to our professional relationship than I first thought. Lyashenko & Frolova (2014: 496) point out that, “intergenerational learning

has always existed since mankind appeared, as knowledge has always been transferred from the old to the young” indicating that support from me helps them learn across generations. However, I further suggest from my experience that this is reciprocal collaboration and support because the students share their experiences on their course, which I am not necessarily familiar with, in addition to how and what helps them manage their studies. I also learned new subjects of study from aeronautics and quantum physics to biochemistry, mathematics and English literature. In addition to learning a new aspect of how they learn or a new digital tool or resource they use, that helps me keep up-to-date and sometimes transfers to support other students (Cohen, 2023). This notion of collaboration and support across generations is upheld by Heffernan et al., (2021) and Dauenhauer et al., (2016) who both indicate that “intergenerational” and “multigenerational” learning needs to be supported as generations

are living longer and more people are engaging in “lifelong learning”. This suggests older generations such as ‘Baby Boomers’ are mixing with younger ones and positively supporting one another, as I do with autistic students (Dauenhauer et al., 2022). Furthermore, a recent online Forbes article by Cohen (2023) states this is the first time there have been “five generations in the workplace”, mostly working collaboratively. Although he also suggests there can be tensions and clashes between generations, but if the younger generation can listen to the older generation, the latter can impart their wisdom. Then the older generation can be

supported by the younger ones to stay relevant and continue evolving and learning. This has helped me see that this is a two-way process of generational reciprocal support and collaboration that happens in my NMH role with autistic students from various universities, studies and needs.

Conclusion

To conclude my autoethnographic reflection on being an NMH helper for the last 5 years in the context of supporting the autistic students at university receiving DSA support, I will consider my reflection, the generational differences and similarities and whether we support each other collaboratively.

Firstly, researching and writing this article has been a rewarding experience and insight into why my NMH role is more effective than I realised for autistic students. This is due to my understanding of their individual needs for academia, professionalism and an open honest non-judgmental approach that supports them within the university culture. In addition to being founded on the fact that I inhabit the shared academic world and I am neurodivergent.

Secondly, the intersections of the socially-constructed concepts of self (being neurodivergent) and education, linked to generational theory and concept are transcended in my role and academia, where collaboration and support across generations, lifelong learning, along with neurodivergent experience converge. This is also supported by the concept of lifespan experiences. Hence commonalities of interest emerge, which in this instance are academia and our life-long learning which are the reasons for our limited differences and similarities. Even though I am at least two generations apart from them, suggesting I would be significantly different to them due to the period I grew up in, the generational divide is overcome by me

being an academic and lifelong learner and thus an apparent anomaly to the theory of generations because I support and collaborate with the autistic students which is, in turn, reciprocated.

Finally, I feel honoured to have supported autistic students over the last 5 years on their academic, as well as life journey and felt appreciated on equal terms.

To conclude, keep on learning, engaging and listening with an open mind and we can transcend generations and neurodivergence expanding this to other areas of our lives.

Differences and Similarities between Generations.

References

Adams, T. E., Ellis, C., & Jones, S. H. (2017). Autoethnography, in The International Encyclopedia of Communication Research Methods, Oxford: Wiley, 1–11.

Berghs, M., Atkin, K., Graham, H., Hatton, C., & Thomas, C. (2016). Implications for public health research of models and theories of disability: a scoping study and evidence synthesis. PUBLIC HEALTH RESEARCH, 4(8), 1–166.

Bolourian, Y., Zeedyk, S. M., & Blacher, J. (2018). Autism and the University Experience: Narratives from Students with Neurodevelopmental Disorders. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 48(10), 3330–3343.

Cohen, Mark. (2023). Learning From Each Other Fostering Intergenerational Collaboration. Forbes, 1–15. Available at: https://www.forbes.com/sites/markcohen1/2023/04/19/learning-from-each-other- fostering-intergenerationalcollaboration/?sh=69be29785d21 Cooper, K., Smith, L. G. E., & Russell, A. (2017). Social identity, self-esteem, and

mental health in autism. European Journal of Social Psychology, 47(7), 844– 854.

Costa, C., Gilliland, G., & McWatt, J. (2019). ‘I want to keep up with the younger

generation’ – older adults and the web: a generational divide or generational collide?

International Journal of Lifelong Education, 38(5), 566–578.

Dauenhauer, J., Hazzan, A., Heffernan, K., & Milliner, C. M. (2022). Faculty perceptions

of engaging older adults in higher education: The need for intergenerational pedagogy.

Gerontology and Geriatrics Education, 43(4), 499– 519.

Dauenhauer, J., Steitz, D. W., & Cochran, L. J. (2016). Fostering a new model of

multigenerational learning: Older adult perspectives, community partners, and higher

education. Educational Gerontology. 42(7), 483–496.

Department for Education. (2023). Department for Education mandatory qualification

and professional body membership requirements to deliver Disabled Students’

Allowance (DSA) fundable Non-Medical Help (NMH) roles. Available at: https://www.

practitioners.slc.co.uk/media/1844/nmh_mandatory_qualifications_a nd_professional_

body_membership_requirements.pdf. Accessed 23 August 2023

Dunn, D. S., & Andrews, E. E. (2015). Person-first and identity-first language: Developing psychologists’ cultural competence using disability language. American Psychologist, 70(3), 255–264.

Ellis, C., Adams, T. E., & Bochner, A. P. (2011). Autoethnography: An Overview. Historical Social Research, 36(4), 273–290.

Ellis, C. and Adams, T. E. (2014) The Purposes, Practices, and Principles of Autoethnographic Research, in The Oxford Handbook of Qualitative Research, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 253–276.

Gunduzalp, S. (2021). Digital Technologies and Teachers in Educational Processes: A Research in the Context of Teachers Born Before the 1980’s. International Online Journal of Educational Sciences, 13(2).

Haegele, J. A., & Hodge, S. (2016). Disability Discourse: Overview and Critiques of the Medical and Social Models. Quest, 68(2), 193–206.

Heffernan, K., Cesnales, N., & Dauenhauer, J. (2021). Creating intergenerational learning opportunities in multigenerational college classrooms: Faculty perceptions and experiences. Gerontology and Geriatrics Education, 42(4), 502– 515.

Hillier, A., Goldstein, J., Murphy, D., Trietsch, R., Keeves, J., Mendes, E., & Queenan, A. (2018). Supporting university students with autism spectrum disorder. Autism, 22(1), 20–28.

HMGovernment (2021) The National Strategy for Autistic Children, Young People and Adults 2021 to 2026, London. Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/national-strategy-for-autistic- children-young-people-and-adults-2021-to-2026/the-national-strategy-for- autistic-children-young-people-and-adults-2021-to-2026.

Gergen, K. J. (2016) The Self as Social Construction. Available at:https://www.researchgate.net/publication/225113163.

Kingstone, H. (2021). Generational identities: Historical and literary perspectives.

Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 15(10). Llewellyn, A., & Hogan, K. (2000). The Use and Abuse of Models of Disability. Disability & Society, 15(1), 157–165.

Lyashenko, M. S., & Frolova, N. H. (2014). LMS projects: A platform for intergenerational e-learning collaboration. Education and Information Technologies, 19(3), 495–513.

Martin, N. (2020). Perspectives on UK university employment from autistic researchers

and lecturers. Disability & Society, 1–21.

McCrindle, M., & Fell, A. (2021). Generation Alpha: understanding our children and helping them thrive. Available at: https://mccrindle.com.au/article/topic/demographics/the- generations-defined/McIlveen, P. (2008). Autoethnography as a Method for Reflexive Research and Practice in Vocational Psychology.17(2), 13–20.

Méndez, M. G. (2014). Autoethnography as a research method: Advantages, limitations and criticisms. Colombian Applied Linguistics Journal, 15(2), 279.

NAS. (2019). Understanding autism online training – National Autistic Society. Online Training NAS. Available at: https://www.autism.org.uk/professionals/training- consultancy/online/understanding.aspx

Parry, E., & Urwin, P. (2011). Generational Differences in Work Values: A Review of Theory and Evidence. International Journal of Management Reviews, 13(1), 79– 96.

Rudolph, C. W., Rauvola, R. S., Costanza, D. P., & Zacher, H. (2021). Generations and Generational Differences: Debunking Myths in Organizational Science and Practice and Paving New Paths Forward. Journal of Business and Psychology, 36(6), 945.

SFE. (2022). Disabled Students’ Allowance (DSA) Non-Medical Help (NMH) provider guidance. Available at: https://www.practitioners.slc.co.uk/media/1879/2122-dsa- guidance.pdf.

SFE. (2023). Guidance for NMH Suppliers. Available at:https://www.practitioners.slc.co.uk/media/1931/nmhguidance_march- 2022_final.,pdf.

Shane-Simpson, C., Brooks, P. J., Obeid, R., Denton, E. G., & Gillespie-Lynch, K. (2016). Associations between compulsive internet use and the autism spectrum. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 23, 152–165.

Strauss, William., & Howe, Neil. (1991). Generations: the history of America’s future, 1584 to 2069 (1st ed.). William Morrow. Available at: https://www.publishersweekly.com/9780688081331

Wall, S. (2006). An Autoethnography on Learning About Autoethnography International Journal of Qualitative Methods 5(2), 146–160.